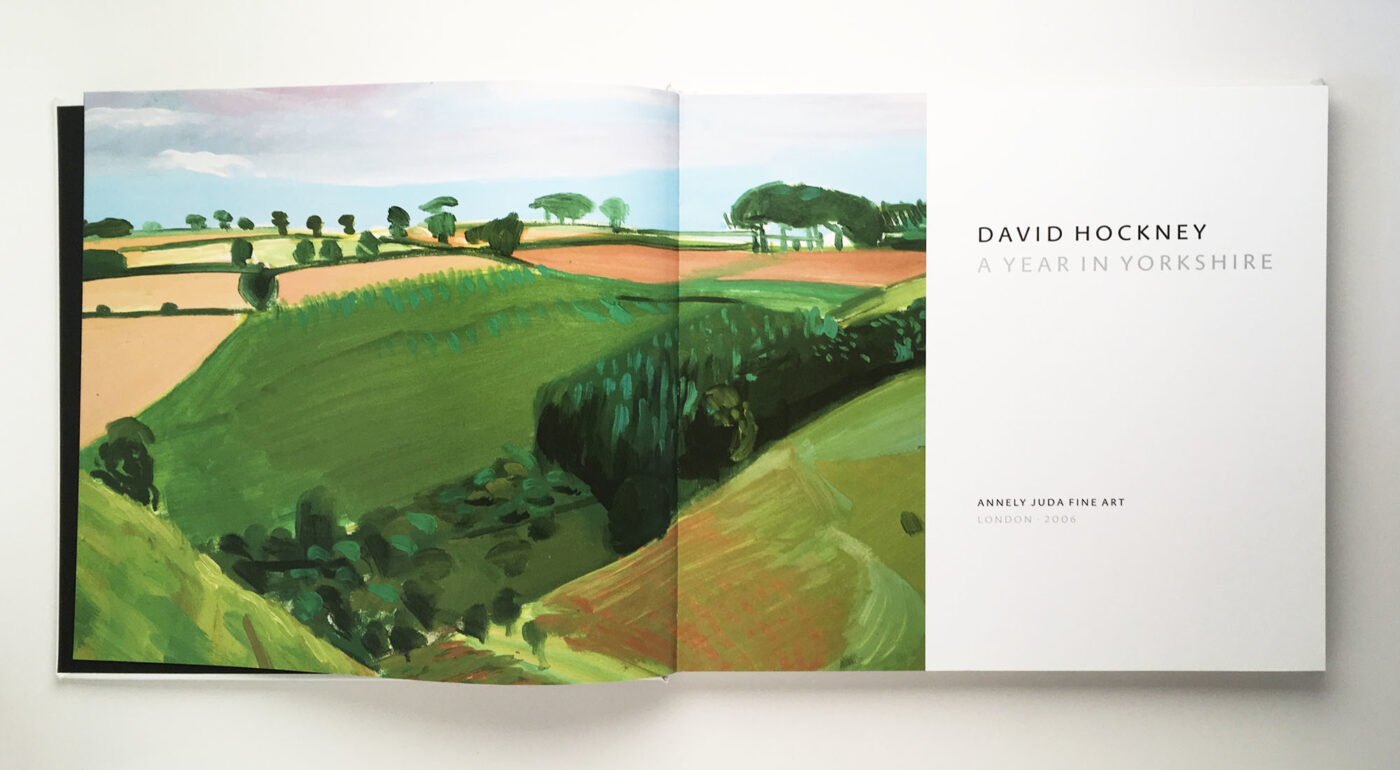

David Hockney

A Year in Yorkshire

Annely Juda Fine Art

2006 | 240 × 265mm | 88pp

I don’t recall if the doorbell actually went ‘ding-dong’, but it was the sort of door that led you to expect it, with its top quarter glazed with a roundel of heavily leaded bumpy glass. The house was a substantial pebbledashed 1930s villa, just around the corner from the sea-front in Bridlington, East Yorkshire, with a white Lexus -saloon parked in front of the detached garage. Suburbia-sur-Mer. On the face of it, it was an unlikely home for David Hockney, far removed from the LA of the 1970s that he had defined in his pictures. His sister had always lived in Bridlington, and he had bought this house for his mother when she was widowed. Now nearly seventy, he had been drawn back to the town where he had spent his childhood holidays after the death of his mother in 1999. With the constant reinvention that had always characterised his art, Hockney had started to paint the landscape of the Yorkshire Wolds, on the spot, in all weathers, and on an increasingly large scale.

Hockney’s London dealer, David Juda at Annely Juda Fine Art, planned an exhibition of these paintings called A Year in Yorkshire, and asked me to meet him with the artist to discuss the catalogue. I travelled from Dunbar by train, changing at York and Hull. The station at Bridlington was a perfectly preserved monument to the age before Dr Beeching, with an absurd superabundance of floral displays to celebrate the fact.

The interior of the Hockney house was in the same high key, with walls of cobalt blue, terracotta and yellow, but the bright June sunshine was dissipated by the dense fug of cigarette smoke. As I went from room to room, introduced by David Juda to the ménage, I noticed that everyone was chain-smoking: DH, his longstanding partner John Fitzherbert, and the exotically named French studio assistant and occasional piano-accordionist, Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima, ‘the only person ever to have left Paris for Bridlington’. There was also a sullen, blond local youth hoovering the stairs, but his main job must have been emptying the ashtrays.

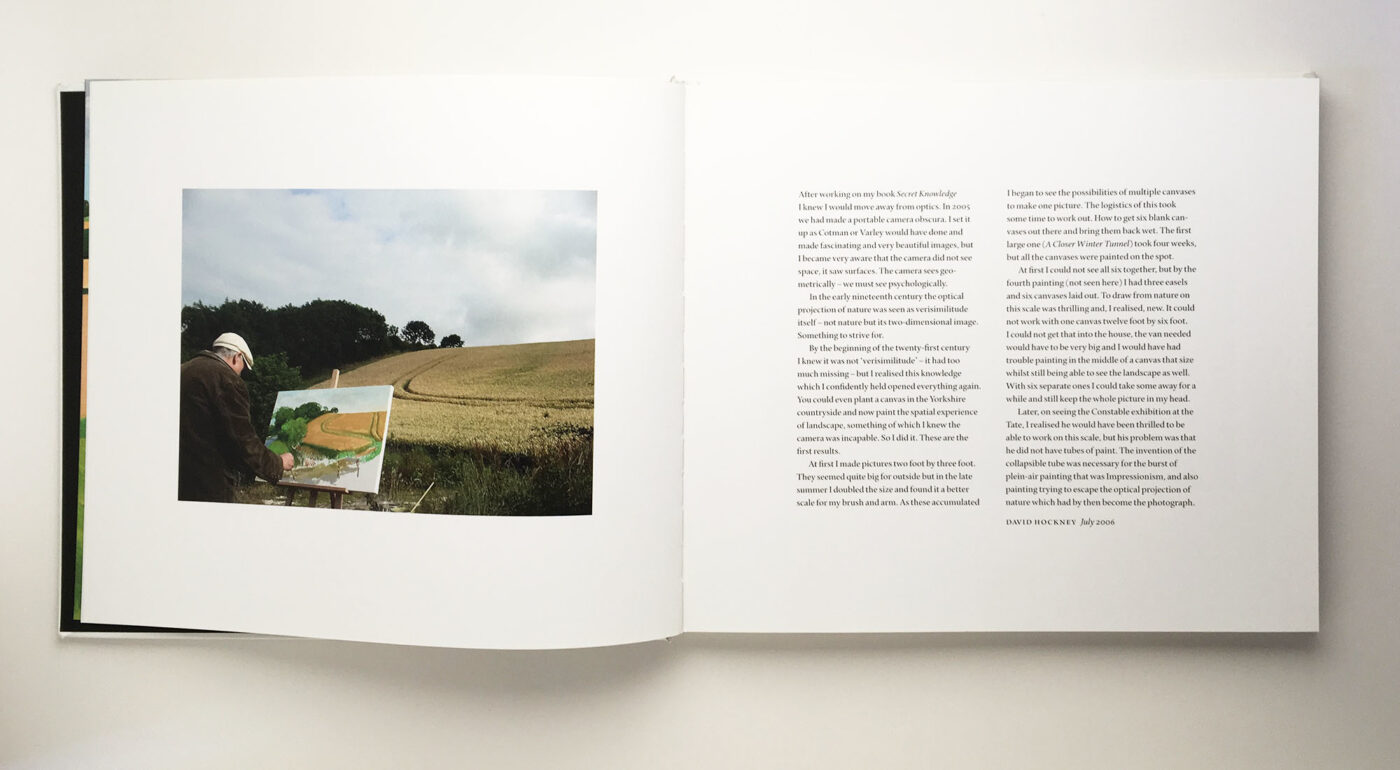

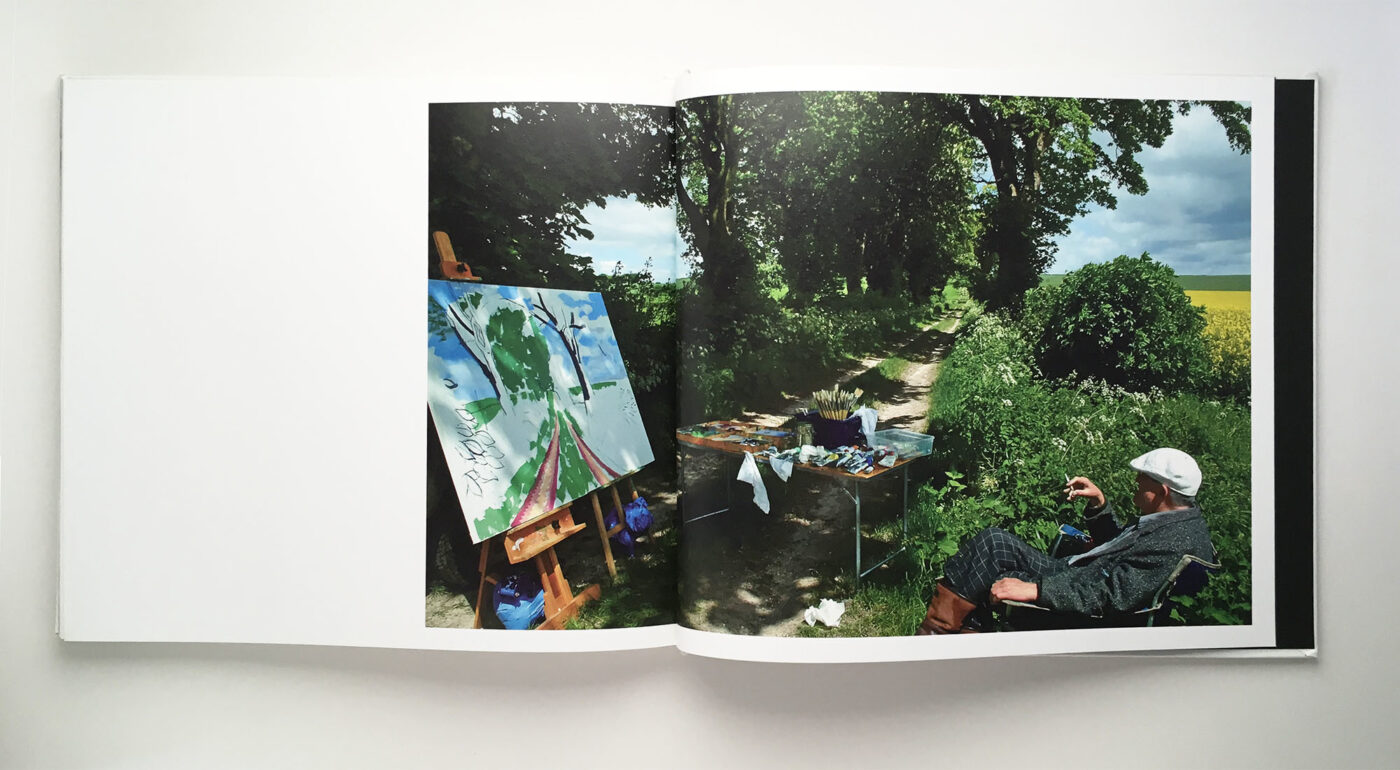

Jean-Pierre had been photographing the painting forays into the countryside around Bridlington and recording Hockney’s work on the paintings in situ. The plan was to include groups of these photographs alongside the paintings in the catalogue, and most of the visit was spent sifting through them and making a selection. In the event only a couple of them were printed; Hockney thought they would detract from the paintings themselves. The still photographs were later superseded by a documentary film called A Bigger Picture, made over three years by Bruno Wollheim and shown on the BBC.

Everything stopped for lunch, prepared by Fitzherbert, a former chef: a freshly baked quiche, salads, cheese and so on. Hockney, as paterfamilias, sat at the head of the table and held forth on all his favourite topics, unimpeded by his deafness thanks to hearing aids in both ears. The conversation ranged from the films of Laurel and Hardy to the merits of the spas of Baden-Baden, but the topic to which he returned obsessively was the iniquity of the smoking ban due to become law in England the following summer. ‘I’ll tell you this, Robert. I’ve been gay all my life, and I’ve smoked all my life. When I was young it was fine to smoke but it was illegal to be gay. Now it’s fine to be gay but it’ll be illegal to smoke. I’ve always been up against it.’ The irony was that a few hours spent in that house was about the best argument for a smoking ban imaginable.

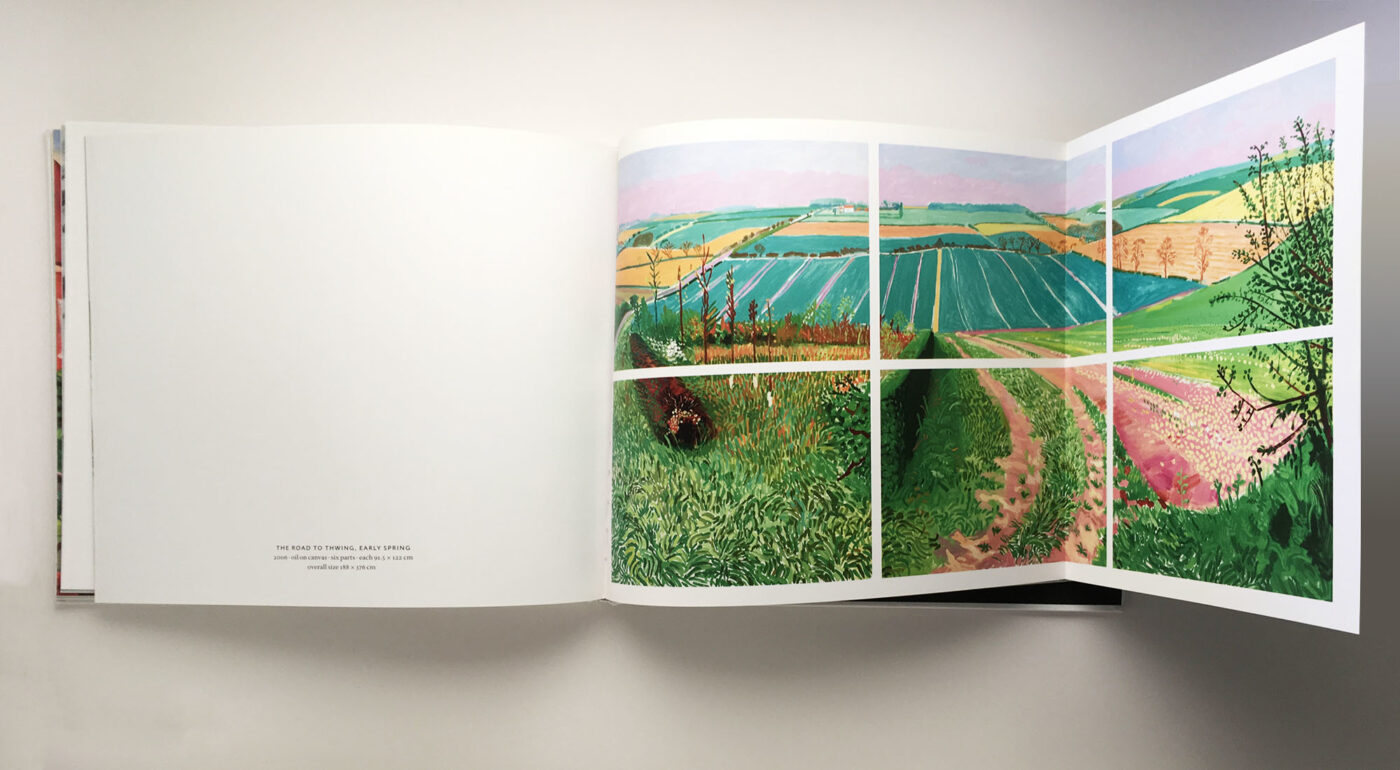

After lunch we went up to the studio created by knocking through the attic rooms and punching large skylights into the north-facing eaves. Most of the paintings for the exhibition were hidden away in a racking system that allowed them to be stored while they remained unfinished, with the paint still wet, until they were taken out into the countryside and worked on in rotation as the weather allowed. When the wind became too strong to keep a 30 x 40-inch canvas on an easel (in spite of the system of weights and guy ropes that Jean-Pierre had devised), Hockney retreated indoors and worked on a painting of the view from the studio windows.

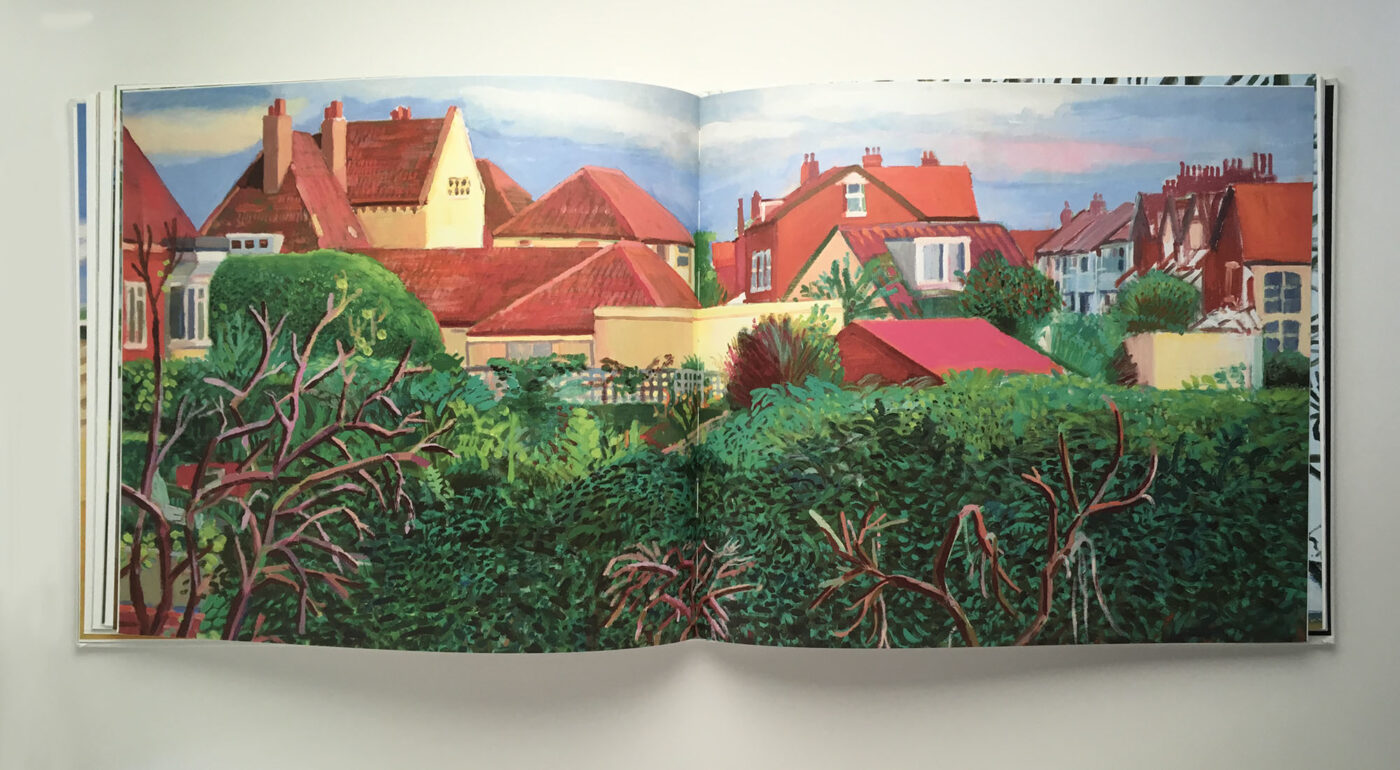

Bridlington Rooftops, October, November, December 2005 was a work far removed from the Californian paintings of the 1970s. Instead of bare-buttocked boys and the spaghetti lines of sunshine on water, Hockney had painted the dreary paved back garden. A bird table stood at the end of a sparse row of evergreen shrubs, probably purchased from B&Q; over the garden wall was an overgrown leylandii hedge, bare at the bottom, lopped off at the top, with the dirty orange and red roofs of the neighbours’ houses beyond. The knowing naivety of the brushwork and the Sunday painter’s use of colour straight out of the tube were rather disconcerting. Were we meant to take this picture-making seriously, or just conclude that Hockney was glad to be home and felt that a prosaic scene required an equivalent style?