Patrick Elliott

and Julian Schnabel

Tracey Emin

20 Years

National Galleries of Scotland

2008 | 265 × 245mm | 152pp

‘Did your designer do that? Don’t tell me … he wears a crocheted scarf.’ And with that, Tracey Emin threw the mock-up of the exhibition catalogue across the room.

Before this episode, I had said to Patrick Elliot, the curator of the Emin exhibition planned at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 2008, that we should prepare some sort of proposal for him to show the artist before our meeting with her. And that, said Patrick, was what Tracey had said when she saw it.

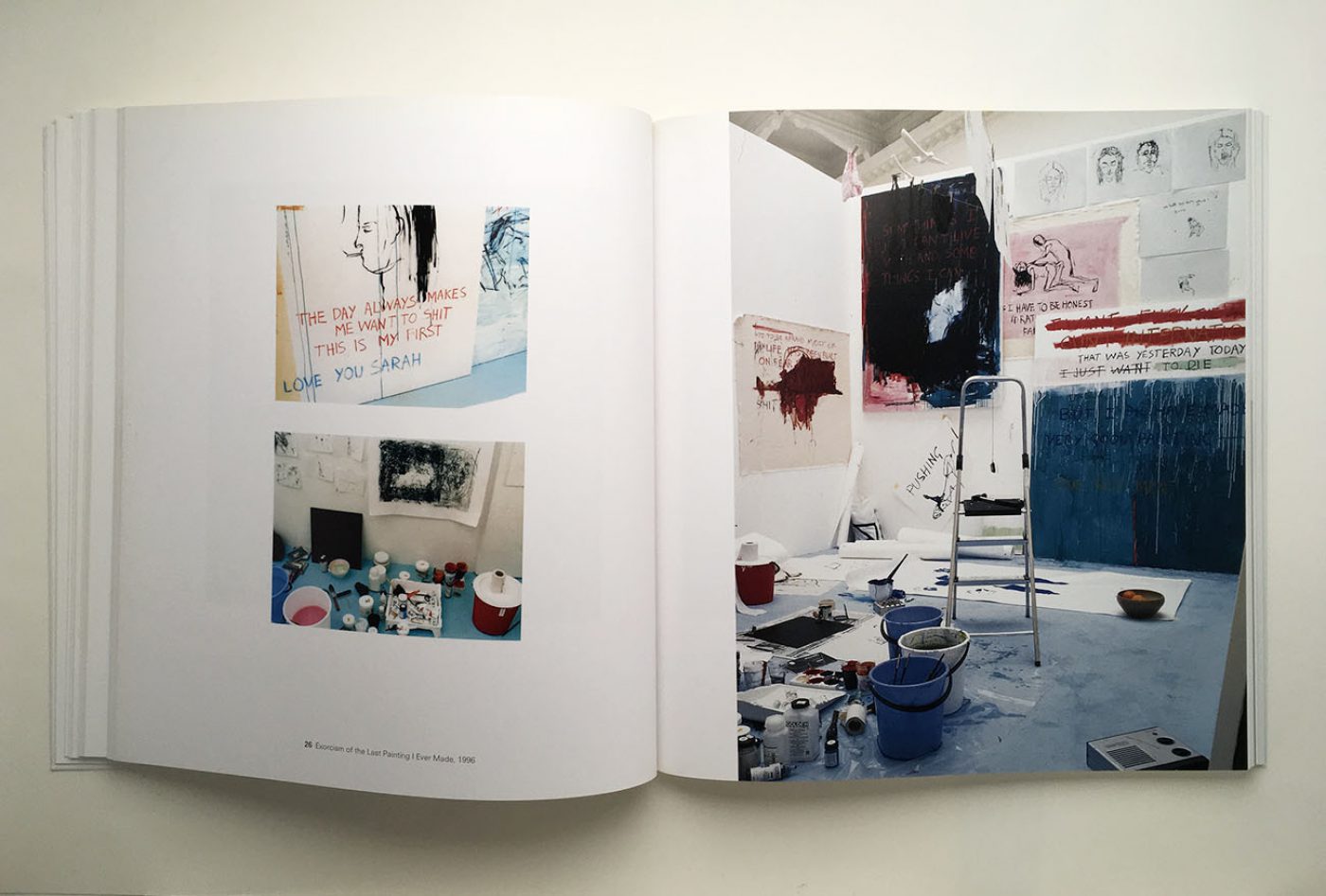

So it was with some trepidation – and with un-usual self-consciousness about my clothes – that I rang the doorbell on the narrow 1960s factory building brashly inserted between the Georgian townhouses of Princelet Street in Spitalfields. (It was seeing the same nervous expression on David Dimbleby’s face as he rang that doorbell in his BBC television series The Seven Ages of Britain of 2010 that made me think I should write down these recollections.) Tracey’s assistant showed me into the studio, said I was the first to arrive, and disappeared. I looked around at the quilts in progress on the walls and the bags of rags and fragments of patterned textiles on the floor that they had been conjured from. One wall at the back of the room was glazed with floor-length Crittall windows that looked on to a vaguely oriental small garden of bamboo and river pebbles beyond. The studio I was in contained a group of oddly assorted chairs – a white-painted fauteuil with flock-velvet upholstery, a cast-iron garden chair, a couple of plastic stacking chairs – and I sat down to wait.

Before long Patrick and Christine Thompson, of the publications department at the National Galleries of Scotland, appeared at the door. Patrick stopped in his tracks and gesticulated wildly. I couldn’t understand what he was trying to convey so he came over and, keeping his voice low, said, ‘Quick, you can’t sit there, that’s Tracey’s chair’.

I just had time to move before Tracey arrived, wearing tracksuit bottoms and a black T-shirt with a plunging neckline, and eating a sandwich, her hair scraped back and still wet from the swimming pool. Later, Christine asked her if there was a public pool nearby: ‘Oh, yeah, but I wouldn’t go there, it’s fillfy. I go to a club, an’, d’you know what, it works out cheaper ’cos I swim every day.’

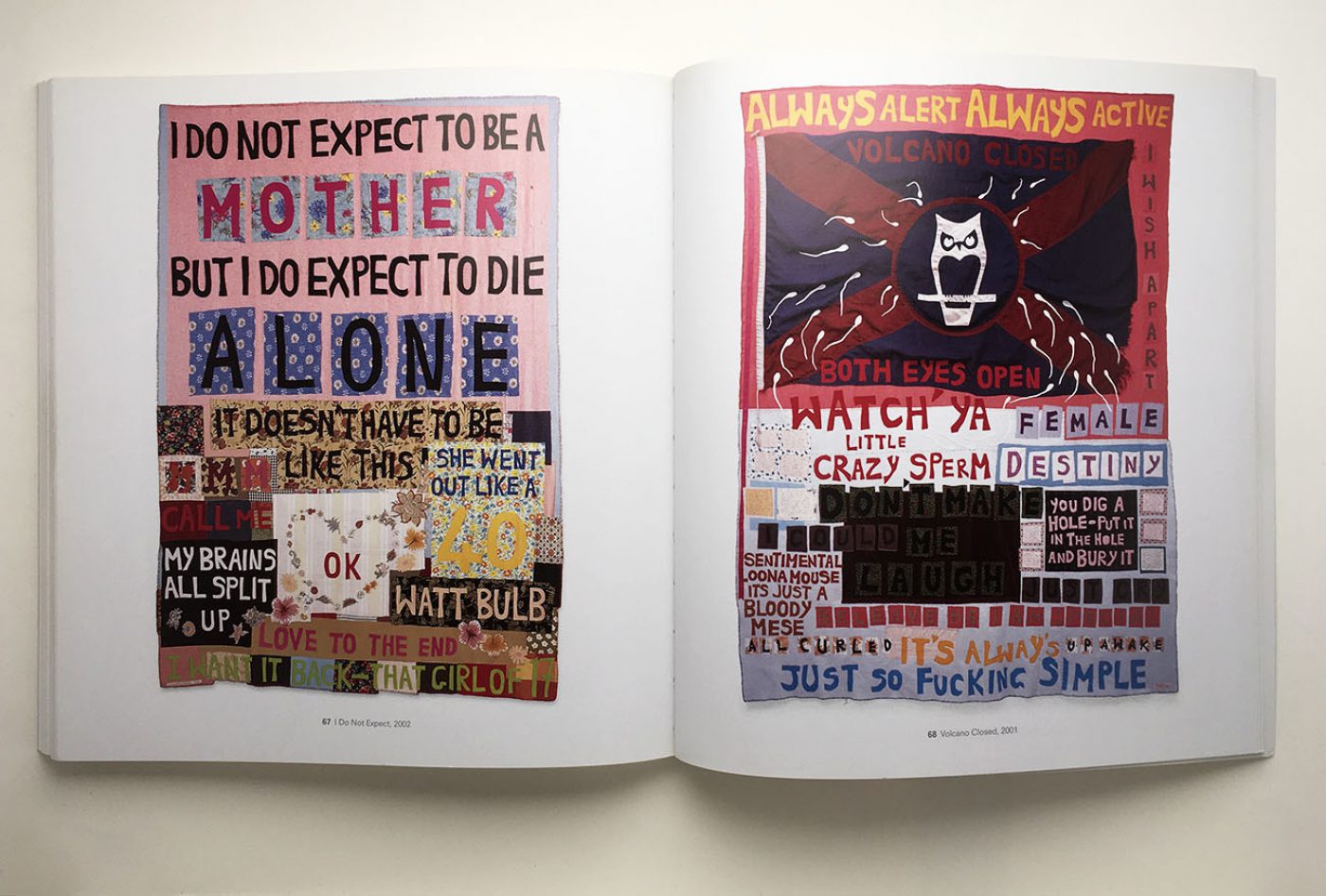

Last to arrive were two representatives from White Cube, Jay Jopling’s definitive YBA gallery, which had plucked Emin out of obscurity in 1994. The gallery had mounted her first exhibition, which with typical chutzpah she called My Major Retrospective 1963–1993. Tracey was fidgety and impatient but absolutely clear in her views about the catalogue. She knew the name of the typeface she wanted the text set in; she knew the paper she wanted the catalogue printed on; she knew the sequence and pairings of the illustrations. She knew she didn’t like any of the faltering suggestions I had made. She made no effort to hide the fact that she was in a bad mood and hadn’t slept well the night before. There was no question that beneath the calm, measured and slightly lisping Essex-girl twang was a ferocious will.

Emin: ‘No, My Cunt is Wet with Fear cannot go there.’

Me: ‘Err, perhaps we should put … that work … on a spread on its own?’

To smooth over the rather sticky proceedings, each time a new work was considered, the White Cube girls soothed Tracey’s ego: ‘Oh Tracey, we are soooo pleased you are including that work, we think it is really important.’ Our progress was slowed by the practicalities of marshalling the international Emin operation. Some recent paintings were still with Gagosian in Beverly Hills; one work was in the RA summer exhibition and wouldn’t be available until after the Edinburgh show opened; one may have been promised to Louisiana. But the good news was that Tracey had seen the American artist and film-maker Julian Schnabel the day before and he was going to write a piece for the catalogue.

Emin’s studio assistant, Alexandra Hill, was a calming influence and helped things along with her practical good sense. She had the brightest blue eyes imaginable and a temperament well suited to a job that must have been highly demanding. All through the afternoon Tracey asked her: ‘What’s my deadline, Alex? How long ’ave I got?’ It was a Thursday and during that period The Independent published Emin’s regular feature, ‘My Life in a Column’, every Friday. ‘The deadline is 7pm,’ said Alex. It was 4 o’clock but no one seemed very surprised that not a word had yet been written.

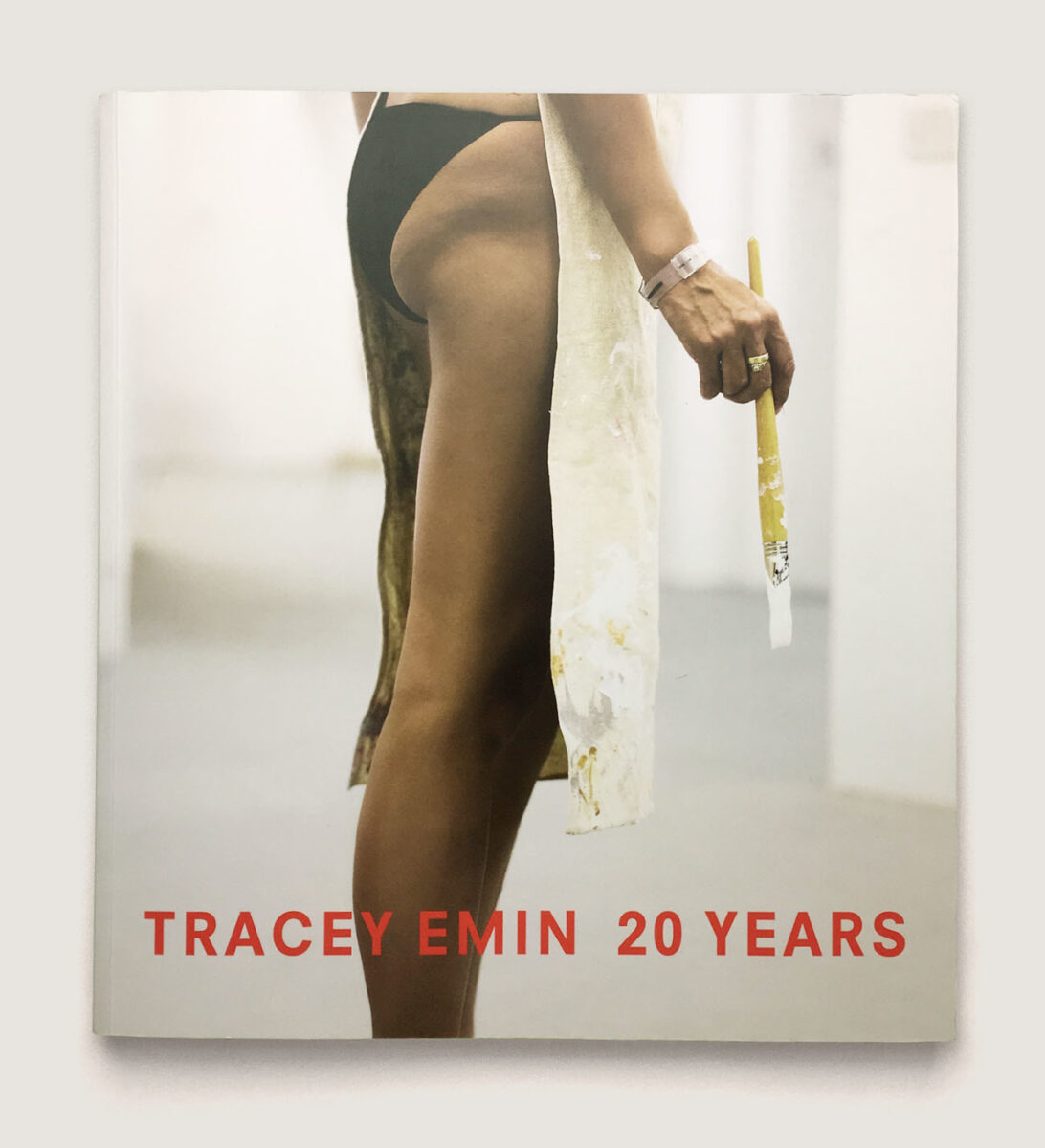

It was a revealing afternoon in many ways. Emin lived up to her reputation as a mouthy prima donna. She was thrilled with the photograph taken recently by her Glaswegian boyfriend, Scott Douglas, showing her from the waist down, dressed in white apron and black knickers holding a paintbrush, which she had decided on for the catalogue cover. ‘My legs look fantastic, don’t they?’ As she pieced together images of the work she had made over a twenty-year span for this retrospective exhibition, talking all the time, it became less easy to be dismissive of it all. The work was Tracey, Tracey was the work. One led imperceptibly into the other and back again like a Möbius strip.

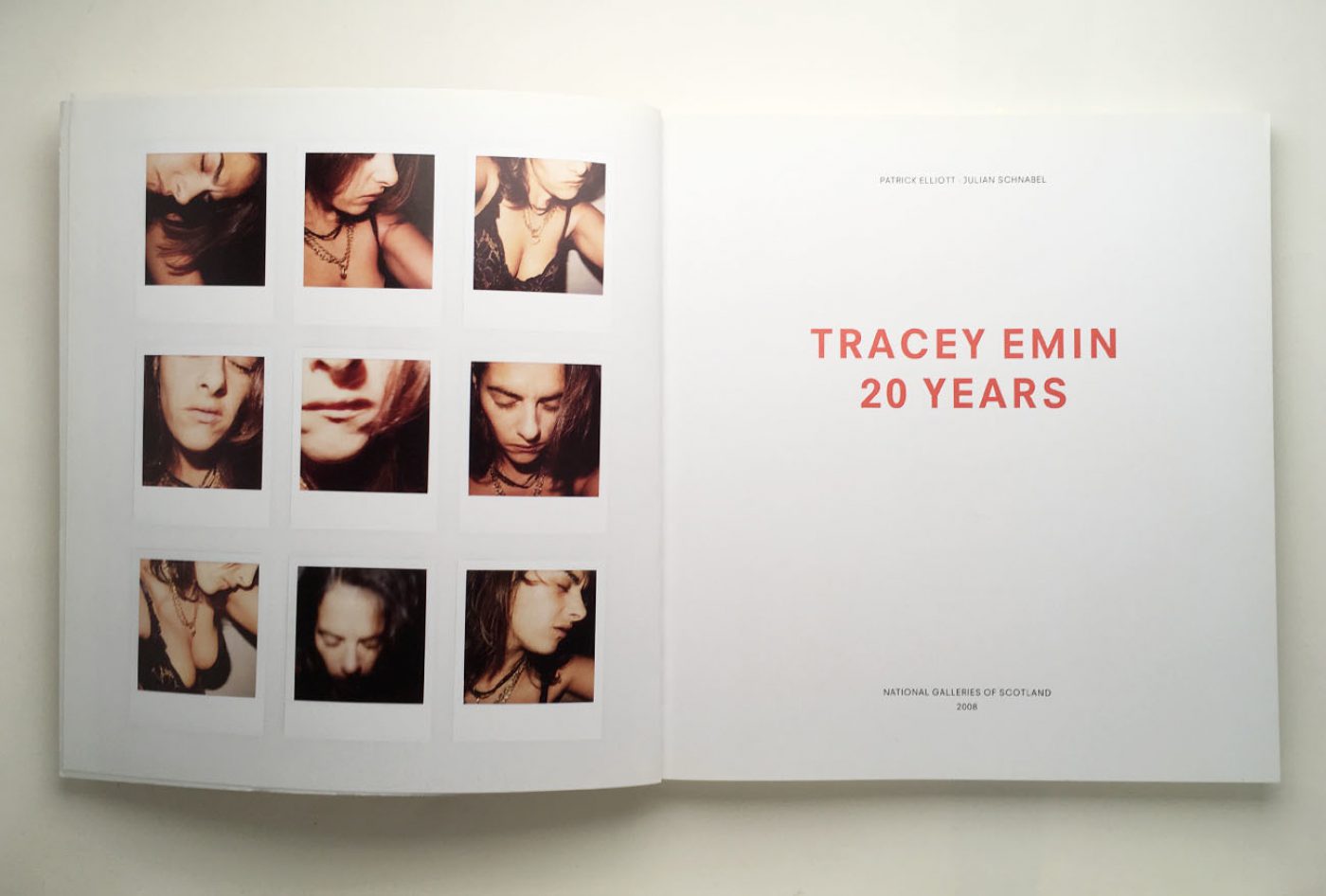

I kept my head down, dutifully noting the order of images, the colour she wanted on the cover, the pictures she wanted to replace. But when she handed over fifty Polaroids that she had taken of herself bent double in an enclosed space wearing only black underwear and suggested that I make a selection to appear opposite the title page, there was no avoiding the task. Was I expected to celebrate her armpit, crotch or navel? Back in Edinburgh the following week, my inhibitions got the better of me and I chose nine images from the neck upwards … with just a hint of cleavage.

At 5 o’clock the meeting broke up, not because we had reached any satisfactory conclusion but because the column could not wait any longer. I left with the sense that I was out of my depth and with a pounding headache. The next morning I opened the hotel bedroom door to find The Independent newspaper lying on the floor. The feeling of trepidation that I’d had when I rang Tracey’s doorbell the day before returned. I opened the paper and leafed through to her column: ‘I seem to be going through mental and physical torture. I’m finding it very hard to be able to relax … I feel that I live in a sea of mediocrity and I’m struggling with emotional ill-adjustment, on my part, and I find it all around me.’ So it was clear what she thought of the meeting and of that designer from Scotland. The article suggested a surprising remedy for her predicament: soup-making. ‘It is one of the few pastimes that makes me feel happy and content.’